A Compass for Navigating Ideaspace

Narrator Are you lost?

Traveller No, I am reading this website.

Narrator You know where you are, in the real world, but what about Ideaspace?

Traveller Ideaspace?

Ideaspace

noun.

Ideaspace is a mathematical model used to describe the mind in a manner congruent with modern physics

Narrator What did you have for breakfast? Was it the same toast as the day before, or maybe you tried something new like a salmon bagel? Naturally toast and bagels are close together in ideaspace: probably right next to eachother. But salmon bagels are further out for sure, but near the same heading.

Traveller I guess now I’m lost and bored.

Narrator Please, allow me to explain. A metric space is defined in math as:

A metric is a function that defines the distance between two points.

- Non-negativity: distances are ≥ 0

- Identity: distance is 0 only if the points are identical

- Symmetry: distance(a, b) = distance(b, a)

- Triangle inequality: going straight is shortest → d(a, c) ≤ d(a, b) + d(b, c)

Traveller So these rules are like the laws of physics, but for a universe of ideas?

Narrator Yes, just like how the laws of physics shape our physical world, these rules shape the world of ideas. Here’s a practical example.

Getting Warmer

The Signal

Narrator Before 1907, Einstein understood gravity the same way everyone else did: Newton’s invisible pull reaching across space.

Einstein recalls this as “the happiest thought of my life”.

A person in free fall feels no gravity, and that’s indistinguishable from being weightless in deep space.

This was a signal.

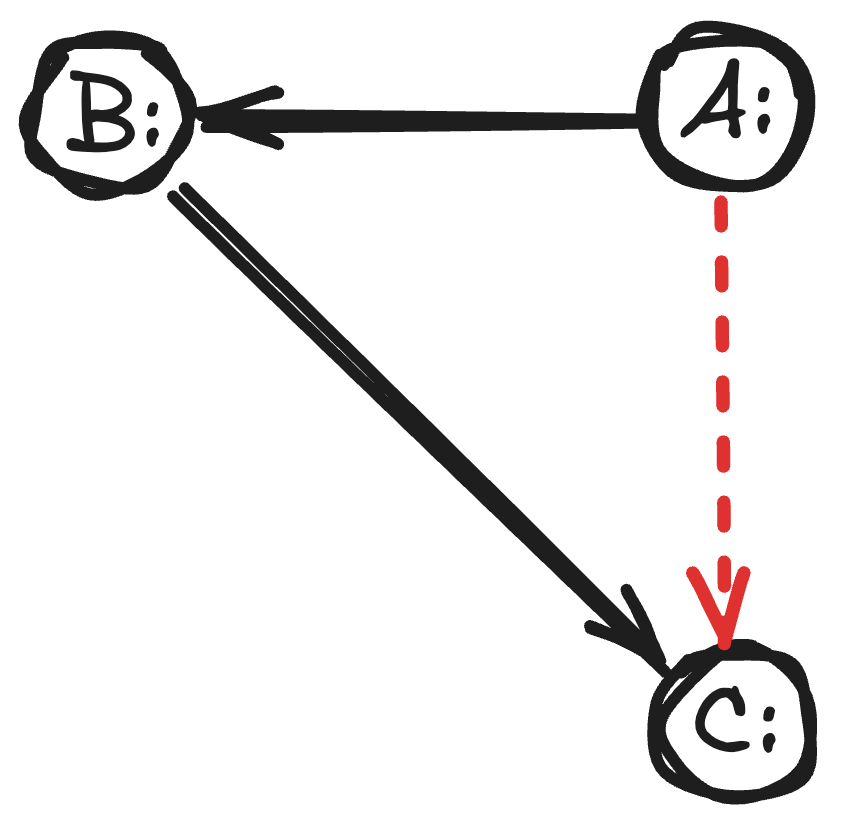

- A: Gravity is a force (Newton)

- B: Free fall weightless (Equivalence)

- C: Gravity is geometry (curved spacetime)

Einstein did not “jump” from A to C overnight. He found a clue that got warmer when he moved in the right direction.

Traveller

No, your analogy is breaking down. If C is the truth, why not just go straight there?

Narrator

Because you can’t “go straight” in a fog. You need something that changes when you make a move. A compass to tell you this step helped.

Einstein didn’t have a map of spacetime geometry. He had a weird, simple test he could carry in his pocket:

If I drop with an elevator, gravity disappears.

This test lit up when he was facing the right way. It didn’t prove General Relativity.

Traveller

So B is like… a hot-and-cold game?

Narrator

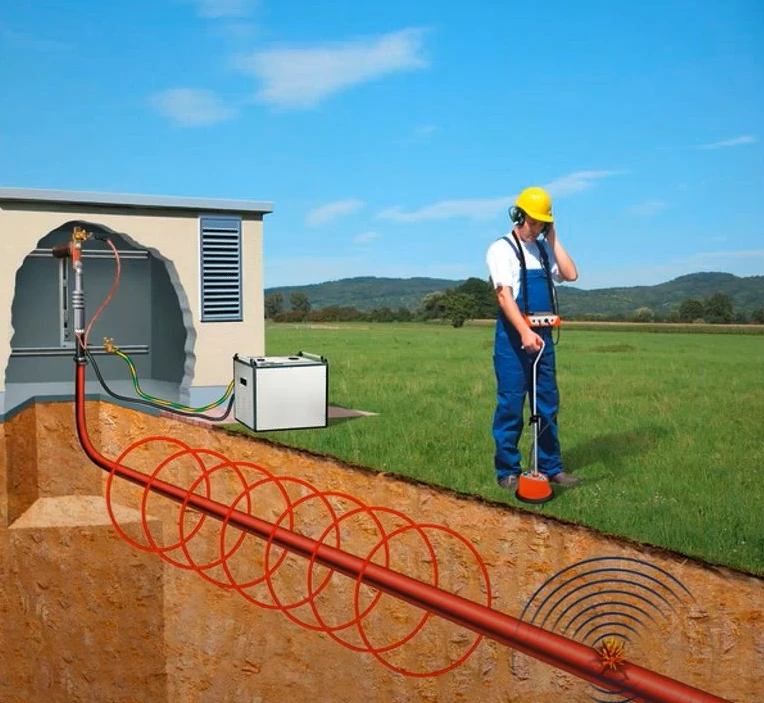

Think about how engineers used to find breaks in underground telegraph cables.

They didn’t dig up the whole city. They didn’t “aim directly” at the break.

They sent pulses down the line and watched what came back. If the reflection changed that means they were getting closer. If there was no feedback then they were getting further away.

Monotonic Signals

Narrator

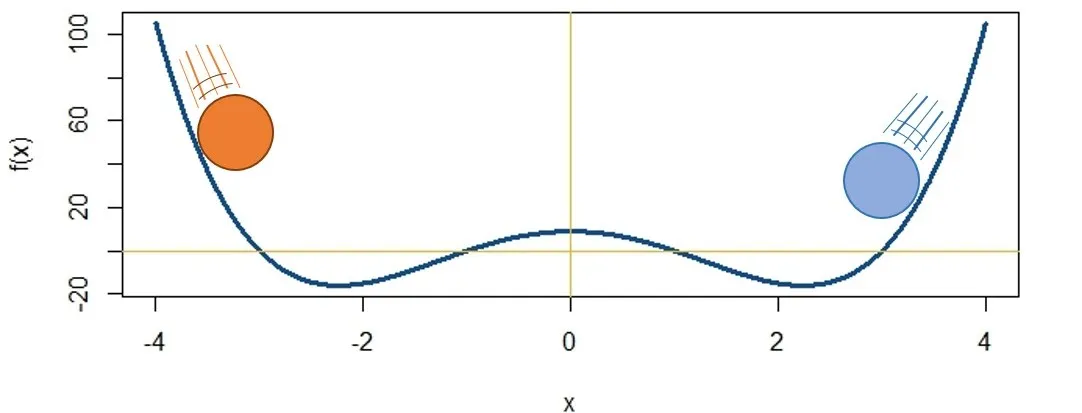

They navigated by a monotonic signal:

the measurement consistently sharpened as you approached the fault.

The measurement is how you keep your sanity while moving through unknown territory.

Einstein’s “elevator thought” was his feedback/reflection pulse:

Curved spacetime wasn’t something he could simply choose at the start.

It was something he had to earn, step by step, by following the signal.

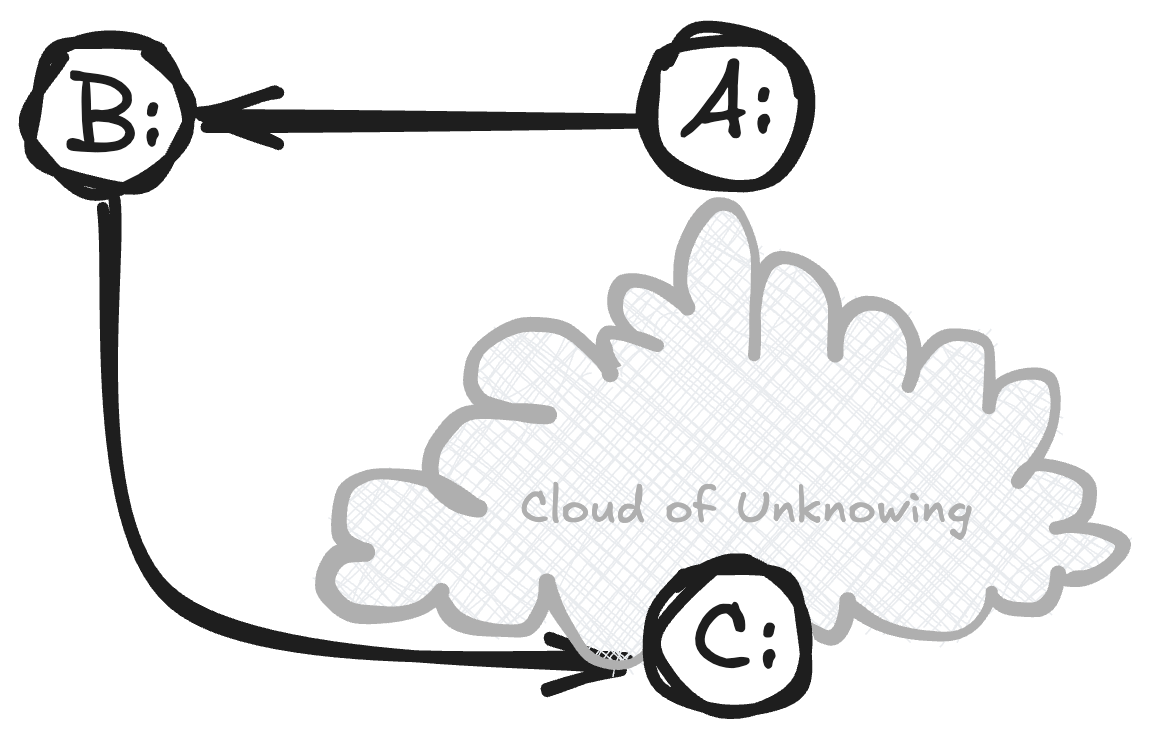

When you’re truly on the edge of ideaspace whether it be at work or in life, it can feel like a grey cloud is blocking your way. You generally know which direction to go but the destination is unclear. This can feel upsetting, tense, anxious and depressing.

Great things are behind the cloud but it’s a fools errand to try and leap over or through the cloud.

When the map is missing, stop trying to travel. Start trying to get warmer.

Find one signal — any signal — that reliably improves as you move. Then take the next step that makes it improve again.

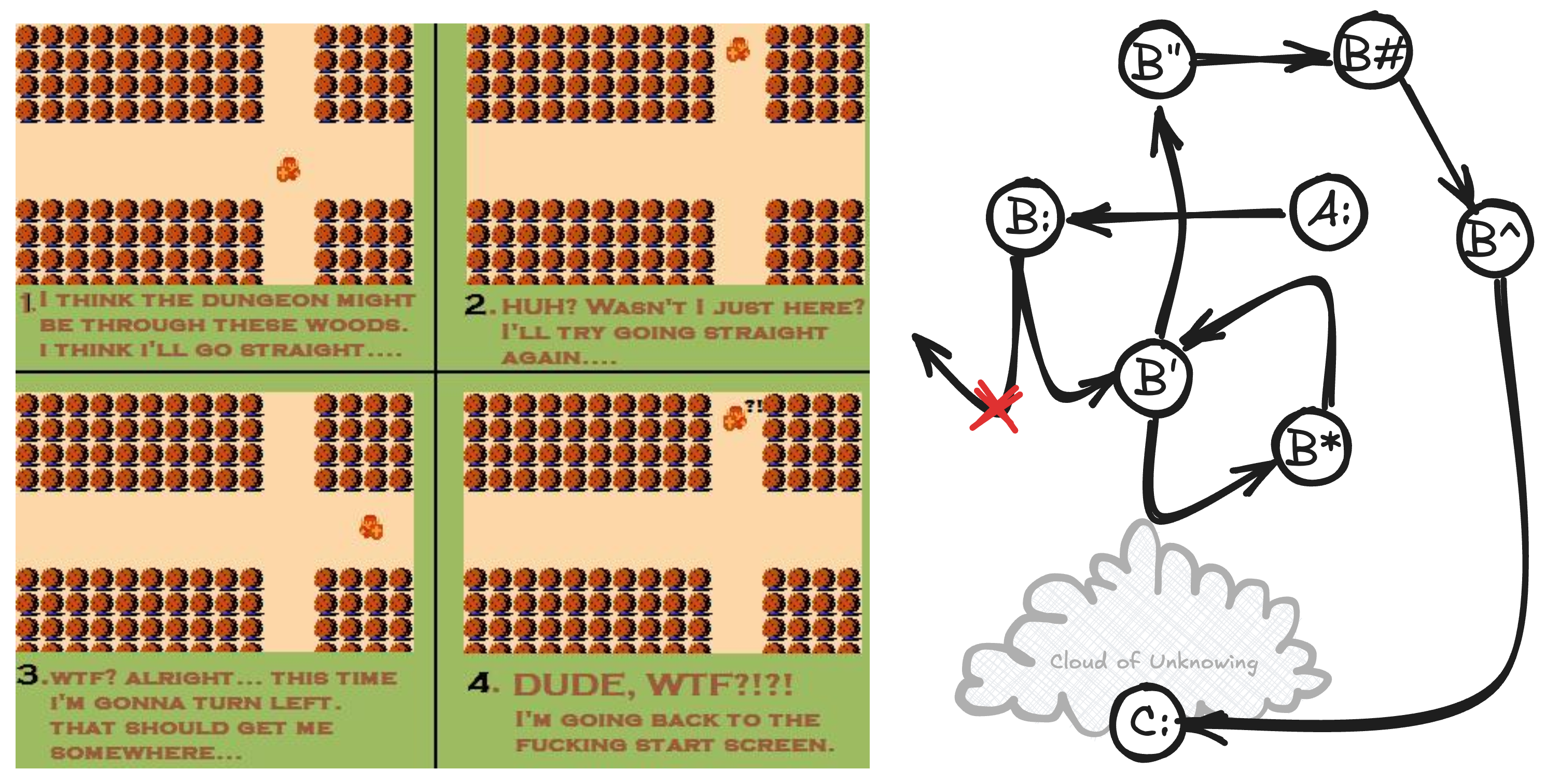

The Lost Woods

Narrator In the Lost Woods from Zelda, every screen has four possible directions, but only one moves you closer to where you want to go.

When you are given this puzzle you begin by going in each cardinal direction at random. This is navigating ideaspace without a reliable metric. You can’t tell how close you are to the exit because every wrong turn loops you back to the start.

Eventually the player notices pattern in the environment, subtle changes in the trees, maybe one is missing. Once you begin recording this, you feel a sense of direction. You do not know where the destination is but you know you are making progress.

Traveller So metrics are really important, huh?

Narrator Yes, and equally so is picking the right ones. If you just listened for changes in the music, counted the pixels in the Link’s sword or tried to notice other unrelated details, the player would have only won through dumb luck.

A Compass for Ideaspace

Traveller So let’s say I’m lost. How do I pick a direction?

Gradient Descent

An iterative optimization algorithm used to find the minimum of a function by taking steps in the direction of the steepest descent.

John D. Carmack II co-founded the video game company id Software and was the lead programmer of its 1990s games Commander Keen, Wolfenstein 3D, Doom, Quake, and their sequels. Carmack made innovations in 3D computer graphics, such as his Carmack’s Reverse algorithm for shadow volumes.

| Carmack subscribes to the philosophy that small, incremental steps are the fastest route to meaningful and disruptive innovation. He compares this approach to the “magic of gradient descent” where small steps using local information result in the best outcomes. According to Carmack, this principle is proven by his own experience, and he has observed this in many of the smartest people in the world. He states, “Little tiny steps using local information winds up leading to all the best answers.” |

Narrator When you’re doing something truly new, it should feel more like exploring. If it’s been done before simply following instructions would cut it.

Take little steps until you find what you didn’t even know you were looking for.